氧化亚氮(N2O)是单分子增温潜势较二氧化碳(CO2)高265倍(100年时间尺度)的强效温室气体,其在大气中寿命可达120 a之久,是平流层臭氧的最主要破坏者[1-2]。19世纪以来,N2O排放量逐渐增加。工业革命前,N2O排放量约为10~12 Tg N·a-1;最新评估结果表明,1998—2016年期间,全球N2O平均排放量约为17.0(16.6~17.4)Tg N·a-1 [3]。N2O减排是全球控制和缓解温室效应的重要组成部分。N2O排放源可划分为自然排放源和人为排放源,自然排放源所产生的N2O排放量约为11.0(10.2~12.2)Tg N·a-1,其中6.6(3.3~9.9)Tg N·a-1来自陆地,3.8(1.8~5.8)Tg N·a-1来自海洋,0.6(0.3~1.2)Tg N·a-1来自大气。由于这部分排放量可以被等量的“汇”所平衡,自然排放对大气中N2O浓度升高的贡献可忽略不计[2]。人为排放源被认为是导致大气N2O浓度升高的主要原因。目前,人为排放量总量约为6.2(5.3~8.4)Tg N·a-1[2],其中农业源N2O排放为4.1(1.7~4.8)Tg N·a-1 [4],是最大的人为排放源;其他人为排放源还包括:工业和化石能源燃烧0.9(0.7~1.6)Tg N·a-1,生物质燃烧(包括焚烧森林和农作物秸秆)0.7(0.5~1.7)Tg N·a-1,废水处理0.2(0.02~0.73)Tg N·a-1,水产养殖0.05(0.02~0.24)Tg N ·a-1,氮沉降至海洋中增加的N2O排放0.2(0.08~0.34)Tg N·a-1,以及其他来源0.05 Tg N·a-1[2]。N2O人为源排放已导致其在大气中浓度较工业化前水平增加了20%,控制农业生产中的N2O排放是减少人为源排放的最重要方面。

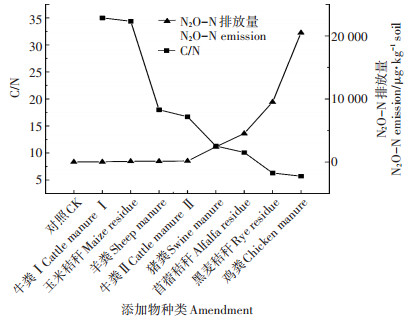

1 土壤是N2O的主要排放源全球N2O排放有66%来源于陆地[3],土壤是N2O的主要排放源。Tian等[5]对工业革命至今的全球土壤N2O排放量的评估结果表明,工业革命前全球土壤N2O排放量为6.3±1.1 Tg N·a-1,其中来源于自然土壤的N2O排放量为6.0±1.1 Tg N·a-1,来源于农田土壤的N2O排放量仅为0.3±0.1 Tg N·a-1,占全球土壤N2O排放总量的5%。近10年来,全球土壤N2O排放量增加至10.0±2.0 Tg N·a-1,其中来源于自然土壤的N2O排放量为6.7±1.4 Tg N·a-1,相比工业革命前仅有0.7±0.5Tg N·a-1的小幅度增加,而来源于农田土壤的N2O排放量则高达3.3±1.1 Tg N·a-1 [5],占全球土壤N2O排放总量的33%(图 1)。

|

(a)长期趋势和变化;(b)相对变化 (a)Long-term trend and variations; (b)Relative change 图 1 1861—2016全球尺度来自农田和其他生态系统的N2O排放[5] Figure 1 Global N2O emissions from cropland and other ecosystems during 1861—2016[5] |

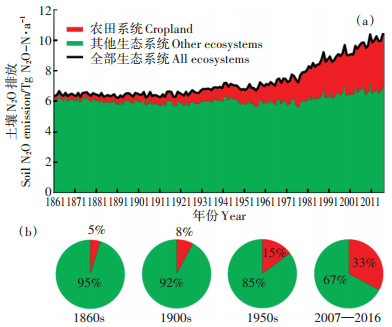

联合国政府间气候变化专门委员会(IPCC)将农田土壤N2O排放划分为直接排放和间接排放[6],其中直接排放主要是由施用化学氮肥和有机肥、作物残体还田、土壤矿化和有机土耕种引起的;间接排放则是由大气中的氮(包括氮肥和动物废弃物中的氮挥发到大气中)沉降到农田,以及氮的淋溶渗漏或径流损失引起的排放[6]。此外,还单独划分了秸秆焚烧和动物粪便的N2O排放。工业革命前至近10年(2007—2016),农田土壤N2O排放增量为3.5±0.9 Tg N·a-1,占全球土壤N2O排放增量的96%[5]。施用化学氮肥和有机肥产生的N2O排放分别为2.0±0.8 Tg N·a-1和0.6±0.4Tg N·a-1,农田施肥引发的N2O排放占土壤总N2O排放增量的70%[5],是全球土壤N2O排放量增加的主要人为因素[7-9](图 2)。因此,合理施氮是减少人为因素导致N2O排放的关键。

|

图 2 1860s—2010s自然和人为因素对全球土壤N2O排放的贡献[5] Figure 2 Contributions of natural and anthropogenic factors to global soil N2O emissions from the 1860s to the 2010s [5] |

农田土壤N2O产生的途径复杂且多样,可划分为生物过程和非生物过程。其中,生物学过程主要包括:自养硝化作用和反硝化作用、硝化细菌的反硝化作用、耦合硝化-反硝化作用、硝酸盐的异化还原作用(DNRA)、异养硝化作用等[10];非生物学过程主要包括:羟胺的化学分解和化学反硝化、亚硝酸盐的化学反硝化、在光照、水分和反应面存在的硝酸铵的非生物分解等[10]。尽管在一些特定的环境条件下非生物过程对N2O产生的贡献较大[11],但生物学过程是N2O产生和排放的主要过程。在大多数条件下,这些过程会同时发生,其主导过程取决于当时的土壤pH、水热条件、氧气状况、碳氮基质等因素及其组合[10, 12-14]。

土壤N2O的排放是N2O在土壤中产生、转化和经过土层向大气扩散的连续过程,任何影响这些过程的因素都将影响土壤N2O的排放速率和排放量。这些因素可大致分为3类,即气候、土壤和农田管理。气候因素包括温度和降雨,会驱动土壤温度和土壤湿度的变化[15-17]。土壤因素包括pH值、质地、土壤氧气浓度以及土壤微生物可利用的C和N的含量等[10, 18-19]。农田管理因素包括种植作物、施肥、灌溉、秸秆管理、耕作等[17, 20]。此外,一些特殊的土壤环境变化也对土壤N2O的产生和排放有重要影响,如土壤的冻-融交替过程[21]和干-湿交替过程[22]。气候、土壤性质和农田管理措施的时空变异是导致农田土壤N2O产生和通量变化的主要原因[23]。因此,要获得准确的农田N2O排放量,需要进行高频率多年多点的田间原位观测。

全球48%人口依赖于氮肥施用增加的粮食[24-25],氮肥对我国粮食增产的贡献约为45%,但不合理施用又带来了诸如水体富营养化、大气污染、温室气体排放等严重的环境问题。我国每年氮肥用量约3000万t,约占全球30%,由此引发的N2O排放占全球N2O排放总额的27% [26]。我国人均耕地少、复种指数高,东部经济发达地区化学氮肥的年施用量达500 kg N·hm-2以上的高投入水平[25]。增施氮肥对我国粮食增产起到了十分重要的作用,但随着氮肥用量快速增加,氮肥增产效果趋于降低,环境污染趋于加重。当前农业生产中,氮肥不合理施用引发的氮素损失增加是一个普遍问题[27-29],我国农田土壤产生的N2O排放中,有77%来自于化学氮肥[30],这也是我国农田土壤N2O总排放量高的主要原因,传统的小农户分散经营方式更加重了氮肥过量施用的问题[27]。因此,将农田氮肥施用量控制在合理水平,在保障产量和农产品品质的前提下,能够实现N2O减排,同时降低其他氮素损失(如氨挥发和硝态氮淋洗)[31]。

农田合理施氮主要包括4个方面,即正确的施肥量(Right amount)、正确的肥料品种(Right type)、正确的施肥时期(Right time)和正确的施肥方法(Right place),国际上称为“4R”理念或技术。这4个方面不是孤立的,而是相互联系的。施肥量首先取决于目标产量,但又决定于肥料品种、施肥时期和方法。其中的任一方面被忽视,都会导致氮素损失使其无法满足作物需求,这也是导致农户现有施肥技术不得不加大施氮量的重要原因。如果后三者均合理,则施入农田的氮肥可以被作物充分吸收利用,就不需要再有额外的氮肥投入以填补施肥过程和施肥后的氮素损失[32]。通过实施“4R”理念或技术,可以更高效地利用养分,使收益最大化并降低人为干预农业养分循环所带来的风险[33],对环境、经济和社会可持续发展做出贡献[34-35]。合理施氮也包括与其他农艺措施的配合,如轮作与耕作、灌溉、有机肥和秸秆还田、磷钾肥和中微量元素管理等[20, 36],以此来提高作物对氮素的利用效率,减少因氮肥施用引起的N2O排放[37]。

3 施氮量与N2O减排 3.1 施氮量与N2O排放量的关系氮素投入是农田土壤N2O排放最具决定性的单一预测因子[38],确定合理施氮量是同类土壤-气候-作物与农田管理措施下N2O减排的最直接措施。在估算区域或国家尺度N2O排放量时,通过整合复杂且多变的全球观测数据,利用统计学方法研究了N2O的季节或年排放总量与主要影响因子的数学关系,IPCC采用了N2O排放量与氮素投入量之间的线性经验模型,将旱作农田土壤的N2O排放量估算为施用到土壤中的化肥氮、有机肥氮或有机质矿化氮的1%(变异范围在0.3%~3%)[6],即排放因子(EF)。这种方法忽略了土壤、气候、作物类型和农田管理措施的时空变异性[33]。

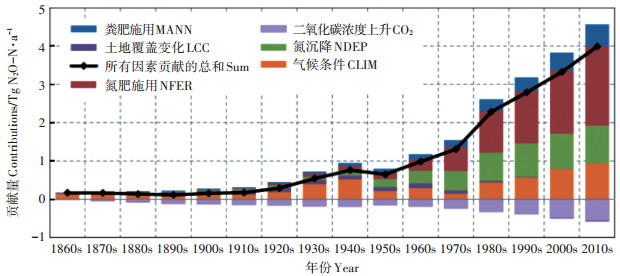

近年来越来越多的研究表明,在特定的土壤-气候条件下,施氮量与N2O排放量之间存在非线性关系[39-41]。在一项涵盖全球78篇论文、涉及233个数据源、至少包含一个不施氮肥处理和两个以上不同施氮量处理的多年多点的Meta分析结果表明,当施氮量超过作物需求时,N2O排放量呈指数增长[42]。美国密歇根州5个地点不同施氮量(0~225 kg N·hm-2)玉米季N2O排放量的研究结果表明,施氮量与N2O排放量之间总体呈现指数关系[43]。在华北平原冬小麦-夏玉米轮作体系中的研究结果表明,玉米季N2O排放量和单位产量N2O排放量均随施氮量增加呈指数增长模式,特别是超过优化施氮水平之后,N2O排放量快速增长。小麦季N2O排放量和单位产量N2O排放量随施氮量增加均呈二次增长模式,且极端降雪引起的冻融交替导致N2O排放强度远大于没有冻融交替发生的年份[20]。通过与经验统计模型对比,发现IPCC固定排放因子及全球旱作农田指数排放模型都高估了华北平原N2O排放,即使在高施氮量的情况下(图 3)。基于大量N2O通量的原位观测结果,Ju等[32]归纳出的华北平原在小麦、玉米和整个轮作的N2O排放因子分别为0.08%~0.21%、0.44%~0.59%和0.10%~0.59%,玉米季排放量远高于小麦季[20, 44-48]。Wang等[49]的Meta分析结果也表明,尽管我国蔬菜作物过量施肥情况较为严重,但其N2O排放因子也仅为0.69%左右,均低于IPCC默认的排放因子(1%)。针对不同施氮量N2O排放的研究结果表明,优化施氮量相对于传统施氮量,可以在降低37%的氮素投入、42%的N2O排放量、44%的单位产量N2O排放量的同时,保持目标产量,此时的氮素盈余量仅为18~37 kg N·hm-2·a-1,远小于传统施氮量的210~220 kg N·hm-2·a-1 [20]。以上研究结果揭示了利用区域尺度模型估算不同土壤-气候条件下N2O排放及减排潜势,进而编制更准确的国家排放清单的重要性。

|

绿色阴影区域代表华北平原玉米和小麦的合理施氮量范围(150~180 kg N·hm-2) Green shaded areas represent the optimum range of N application rate(150~180 kg N·hm-2)for maize and wheat in the North China Plain 图 3 华北平原与全球尺度施氮量与N2O排放关系的比较[20] Figure 3 Comparison of N2O responses to N application rates in the North China Plain or the global scale[20] |

淹水稻田是我国另一种主要耕作方式,由于土壤水分管理方式的不同,水稻生长季土壤N2O排放格局和排放量明显不同于旱地。IPCC[6]提出稻田的N2O默认排放因子为0.3%(变异范围在0%~0.6%),但其并未区分不同水分管理方式。Zou等[50]和邹建文等[51]将中国稻田划分为持续淹水(F)、淹水-烤田-淹水(F-D-F)和淹水-烤田-淹水-湿润灌溉(F-D-F-M)3种不同的水分管理模式,不同模式下的N2O排放因子分别为0.02%、0.42%和0.74%。我国不同地区农田氮肥施用、作物类型和土壤气候条件差异很大,同样的氮肥施用量所导致的N2O排放量会有较大的区域性差异,通过直接测定特定土壤-气候条件、种植制度和农田管理措施下的N2O排放量,建立同类地区施氮量与N2O排放量之间的数量关系,对于更准确地评估区域和国家尺度的N2O排放量、制定更有针对性的N2O减排措施至关重要。

3.2 合理施氮量的确定确定合理施氮量是获得较高目标产量、维持土壤氮肥力和降低因施氮引起环境污染的关键[52],是氮肥发明和施用以来的世界性难题。其方法可归纳为:(1)基于田间试验作物产量对施氮量响应的肥料效应函数法;(2)基于土壤或植株测试的测试类方法。但是,这两类方法在实际应用中均有较大缺陷[53]。归其原因,主要是缺乏对肥料氮、土壤氮、作物吸收氮等物理量之间数量关系的彻底解析。Ju等[54]基于对土壤-作物体系中氮素的详细流动通量,提出了理论施氮量(TNR)的概念和方法。在考虑了包括干湿沉降、生物固氮等其他来源氮之后,发现了“合理施氮量约等于作物地上部吸氮量”的普遍规律[52]。在引入百千克收获物需氮量(N100,kg)参数后,合理施氮量是目标产量(Y)的唯一函数,即理论施氮量Nfert≈Y/100×N100。其中目标产量和百千克收获物需氮量的确定取决于同类地区的生产条件,包括气候、土壤、作物和农田管理措施等。理论施氮量从长期维持高产稳产、土壤氮素平衡和低环境风险考虑,推广技术员和农户能够根据自己地块的目标产量用口算确定出施氮量,提供了一种简便实用的方法[52, 54]。

如何判断农田氮素管理是否合理,是改善氮素管理的关键,其中一个重要的方法是发展氮素管理指标。氮素利用率(NUE)一直被广泛使用,但该指标并不能反映产量水平和氮素损失量。片面追求较高的氮素利用率不一定能够实现目标产量和低的氮素损失。欧洲一些国家一直强调NUE必须和其他指标,如氮素盈余和作物收获氮等指标结合,来判断氮素管理的优劣。在作物生产中,氮素盈余指“向作物投入的氮与作物收获氮的差值”。过高的氮素盈余意味着高氮素损失风险,过低的氮素盈余可能造成土壤氮素消耗从而不利于可持续作物生产。因此,必须把氮素盈余控制在合理的范围内。基于在我国不同农业生态区多年多点的田间试验,Zhang等[32]建立了13种作物体系的氮素盈余指标,同时建立了与NUE和作物收获氮之间的关系。一年一熟作物体系的氮素盈余标准为40~100 kg N·hm-2·a-1(平均为73 kg N·hm-2·a-1),而一年两熟作物体系的氮素盈余标准为110~190 kg N·hm-2·a-1(平均为160 kg N·hm-2·a-1),约为一年一熟作物体系的两倍[31]。在严格执行“4R”理念或技术,并改进施肥技术和农田管理措施的条件下,氮素沉降和活性氮的损失可以进一步下降,氮素盈余标准也可以进一步降低。基于这些指标,政策制定者、科研人员及农户能够客观地评估和提高不同田块的氮素管理水平,实现目标产量、品质和低氮素损失[31-32, 55]。

4 肥料品种与N2O减排根据目标产量和维持土壤氮素平衡确定了合理施氮量后,选择适合的氮肥种类也有利于减少农田土壤N2O排放。但确定好合理的施氮量始终是首要问题,只有在确定了合理施氮量的条件下,才可以通过选择和改进肥料种类实现进一步的减排。目前,我国农田常用氮肥主要为尿素、硝态氮肥和铵态氮肥,这些氮素形态被加工成不同的氮肥种类。不同肥料种类的减排效果取决于土壤、气候、作物和农田管理措施,不能一概而论[56]。应该研究不同土壤-气候-作物体系下,包括控释肥和缓释肥、各种肥料添加剂及生物炭,也包括有机肥和秸秆的配合施用等在内的具体肥料种类的N2O减排效果。

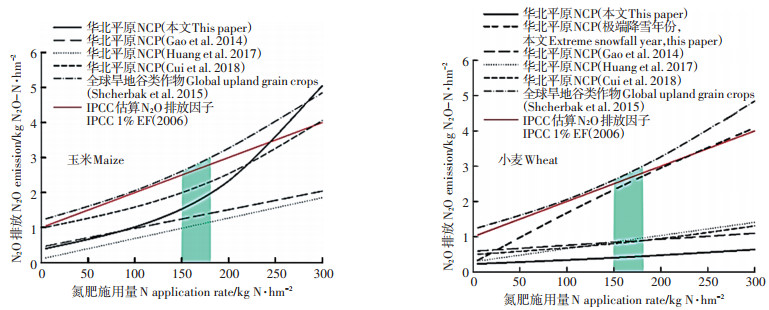

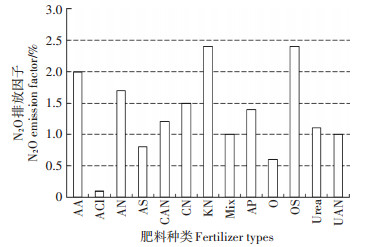

联合国粮农组织和国际肥料工业协会发布的报告[16],统计了化肥和粪肥施用引起的N2O排放(图 4)。不同肥料种类的N2O排放因子范围为0.1%~2.4%[16]。其中,有机肥和化肥混合施用的排放因子最大,这可能是由于有机肥的投入提供了大量有机碳,加强了土壤微生物的活动,营造土壤厌氧状态,增强了反硝化作用[57-58];与此同时,化肥投入又为微生物提供了大量氮源,进而导致了大量的N2O排放,但这种情况更容易在欧洲的降雨量较高、土壤经常处于湿润条件下发生[58-59],在其他旱作土壤-气候-作物条件下,值得进一步研究。液氨、磷铵和尿素施用后会引起土壤pH的改变,pH的增加促进了硝化作用强度,促进了N2O排放[60]。

|

AA:液氨;ACl:氯化铵;AN:硝酸铵;AS:硫酸铵;CAN:硝酸铵钙以及硝酸铵和碳酸钙的混合物;CN:硝酸钙;KN:硝酸钾;Mix:混合肥料;AP:磷铵;O:有机肥;OS:有机肥和化学肥料混合施用;Urea:尿素;UAN:尿素硝铵 AA: Anhydrous ammonia including aqueous ammonia; ACl: Ammonium chloride; AN: Ammonium nitrate; AS: Ammonium sulphate; CAN: Calcium ammonium nitrate and combinations of AN and CaCO3; CN: Calcium nitrate; KN: Potassium nitrate; Mix: Mix of various fertilizers; AP: Ammonium phosphate; O: Organic fertilizers; OS: Combinations of organic and mineral fertilizers; Urea: Urea; UAN: Urea-ammonium nitrate 图 4 不同类型肥料的N2O排放因子[16] Figure 4 N2O emission factors of different types of fertilizers[16] |

同一氮素形态在不同的土壤-气候-作物体系的N2O产生和排放存在较大差异。排水良好的旱作农田施用硝态氮肥排放的N2O低于施用铵态氮肥或尿素[61-62]。我国华北平原冬小麦-夏玉米轮作体系中,夏玉米季硝态氮肥的N2O排放因子仅有0.006%,远低于施用尿素的N2O排放量[63]。温暖湿润环境下,不同形态的氮肥均具有较高的N2O排放量;而低温潮湿环境下,施用铵态氮肥相比于施用硝态氮肥可以降低N2O排放[64]。稻田不同氮肥N2O排放表现为液氨>铵态氮肥>硝酸钙>硝酸铵>尿素[65]。不同种类氮肥在土壤中NO3-与NH4+的时空变化,会引起土壤N2O排放通量的变异。施用哪种肥料有利于N2O减排,应根据同类区域土壤-气候-作物体系和其他农田管理措施,结合产量、农产品和其他氮素损失途径综合考虑。

有机肥施用和秸秆还田也是农田土壤N2O排放的主要来源[66],其对N2O排放的影响结果并不一致。如上所述,有些研究表明,相比于施用化学氮肥,有机肥和秸秆的施用会增加土壤N2O排放[48, 58, 67-69]。我国华北平原的田间试验结果表明,有机肥(牛粪)的施用使冬小麦-夏玉米轮作体系的N2O排放增加了17.2%[37]。不同来源有机肥由于C/N的差异,导致土壤DOC和无机氮含量差异而影响N2O的产生与排放。通常情况下,农田土壤N2O排放量与有机肥的C/N呈负相关(图 5),这也很好地解释了为什么相比其他动物粪便,家禽粪便的施用会诱发更高的N2O排放量[68-70]。尽管施用有机肥可能会增加N2O排放,但在合理施氮条件下利用有机肥替代部分化学氮肥,既可以通过增大土壤有机碳库,增强土壤的缓冲性能、改善土壤肥力降低氮素损失[36];又可以通过减少化学氮肥输入而降低农田土壤N2O排放总量[71]。

增效肥料(Enhanced-efficiency fertilizer)的施用,在一定条件下对N2O减排有积极作用,但不同土壤-气候-作物体系的效果差异较大[72-73]。增效肥料主要包括:脲酶抑制剂(Urease inhibitor,UI)、硝化抑制剂(Nitrification inhibitor,NI)和控释肥(Controlled-release N fertilizer,CRF)。根据不同土壤-气候条件选择合适的增效肥料种类,可以提高产量和氮素利用率,减少氮素损失,降低N2O排放。不同增效肥料N2O减排效果存在较大差异,总体表现为:UI<CRF<NI[56, 72-73]。Akiyama等[72]的Meta分析结果表明,与施用普通肥料相比,UI的N2O减排效果并不显著,但CRF和NI分别可以降低35%和38%的N2O排放。UI通过抑制尿素水解,减缓其向NH4+的转化,降低NH3挥发。土壤和环境条件越易于造成NH3挥发损失,UI对肥料氮素的保持能力越强[74]。CRF对稻田N2O减排效果优于旱地土壤,Xia等[75]的研究结果表明,施用于稻田的CRF可以减少50.4%的N2O排放量,而施用于旱地农田仅减少25.3%。CRF需要氮素释放速率与作物对氮素需求同步[72],否则也有可能增加N2O排放[37]。火山灰土上施用CRF仅能降低3%的N2O排放量,但其他土壤类型平均可降低24%,并且传统施肥处理产生的N2O排放量越大,CRF的减排效果越好[76-77]。

NI可以通过延缓氨氧化过程[78]来降低硝化速率,协调肥料供氮与作物需氮,同时降低反硝化底物,达到降低N2O排放的目的。常见的NI有:双氰胺(DCD)、3,4-二甲基磷酸盐(DMPP)和四氮本啶(Ni-trapyin)等。NI平均可降低38%的农田N2O排放,但不同土壤-气候-作物和NI种类的减排效果存在显著差异[72]。旱作农田施用NI可以降低34%~57.7%的N2O排放量;而施用于稻田的NI可降低30%~33%的N2O排放[56, 75]。我国华北平原典型潮土的田间试验结果表明,相比单施尿素和硝酸铵,DMPP分别可以减少77%和68%的N2O排放[44, 79]。农业土壤上施用DCD的N2O减排效果虽略低于DMPP,但平均也可以减少30%的N2O排放量[72],DCD对N2O减排效果受温度、土壤黏粒含量与土壤有机质之间的显著影响[80]。传统施肥产生的N2O排放量越高,NI的减排效果越好[56]。NI可以同时作为化学氮肥和有机肥的添加剂,且均可以达到一定的N2O减排效果。值得注意的是,NI会增加NH4+在土壤中存留时间,平均可增加氨挥发30%左右[75],特别是在pH高的碱性土壤上。因此,研究同时降低NH3和N2O排放的农田管理措施显得更为重要。有些研究试图将脲酶抑制剂和硝化抑制剂混合施用以发挥多种损失协同减排的效果。由于两者作用的生化反应步骤不同,两种抑制剂在一起施用也有可能发生化学反应而失效,双抑制剂并没有发挥“1+1>2”的作用[81-84]。因此,混合施用必须根据土壤-气候-作物特征和施用条件、肥料品种、有充分的理论依据和试验证据,切忌想当然。

5 施肥时期和方法与N2O减排在确定了合理施氮量和肥料种类后,施肥时期和方法就成为提高氮素被作物吸收利用、减少农田氮素损失和N2O排放的重要环节。合理的施肥时期应尽可能保证氮素供应与作物的需肥时期同步。确定合理的施肥时间需考虑作物养分吸收、土壤养分供应、环境风险及田间操作的相互影响。关于氮肥施用时期对N2O排放影响的专门研究资料较少。我国华北平原冬小麦-夏玉米轮作体系中,每年10月初冬小麦播种和施用基肥的N2O排放均明显低于春季追肥,也明显低于夏玉米季施肥[20, 42-43, 48, 85]。夏玉米季等氮量追肥,多次追肥的N2O排放量可能高于一次或两次施肥[45, 85]。施肥时期对N2O排放的影响,受当时土壤的水热条件、作物生长时期的严重影响,应结合其他农田措施综合考虑。

由于受耕作方式、肥料状态和作物生育时期的影响,生产上存在多种施肥方法。不同施肥方法对氨挥发损失和作物氮素利用的研究较多,但对N2O减排的研究较少。从减少氨挥发损失和提高作物氮素利用的角度考虑,氮肥深施是施肥的基本原则。NH3和N2O都是重要的环境气体,深施氮肥能有效减少NH3挥发损失,但可能增加N2O排放。Rochette等[86]的研究结果表明,当施肥深度大于7.5 cm时,氨挥发损失很低可忽略不计;但深施处理的N2O排放量显著高于撒施[87]。刘敏等[88]在华北平原的研究结果表明,尿素深施或条施可以减少69%的NH3挥发损失,但会使N2O排放量增加2倍。施氮量相同的条件下,不同施肥方法N2O排放量总体表现为:穴施>条施>撒施[89]。考虑到NH3沉降带来的间接N2O排放,NI在减少N2O直接排放方面的有益作用可能会被NH3挥发的增加所削弱,甚至超过[90]。需要研究不同土壤-气候-作物体系中,施肥时期和施肥方法对作物氮素利用、各种损失途径的综合效应,找出同时降低氨挥发、硝酸盐淋洗和N2O排放的措施,避免各个损失途径的“Trade-off”效应。

6 结语N2O减排主要是减少人为源的排放,农田土壤是减排的主要方面。其中土壤、气候因素是不可控制的,只能通过农田管理措施来调控N2O排放速率、季节排放量、全年总排放量,或者单位农产品排放量。农田管理措施包括作物、施肥、灌溉、耕作和秸秆管理等多个方面,其中合理施氮是减少N2O产生和排放的最直接因素。合理施氮既包括“4R”理念或技术(施氮量、肥料种类、施肥时期和方法),也包括与其他农艺措施的配合,如轮作与耕作、灌溉、有机肥和秸秆还田、磷钾肥和中微量元素管理等。将施氮量控制在合理范围内,既能获得目标产量和应有的农产品品质,也能将氮素损失(氨挥发、硝酸盐淋洗、N2O排放)降低到环境可承受的范围内。根据目标产量和维持土壤氮素平衡确定了合理施氮量后,选择适合的氮肥种类也有利于减少农田土壤N2O排放,但确定合理施氮量始终是首要问题,只有在合理施氮量的范围内,才可以通过选择和改进肥料种类实现进一步减排。脲酶抑制剂、硝化抑制剂和控释肥等增效肥料的研发和应用,也为减少农田N2O排放提供了途径,但减排效果取决于土壤-气候-作物和农田管理措施。合理施肥时期和方法,可保证施入农田的氮素被作物充分吸收利用,提高氮素利用率而降低N2O排放,但需注意氮素不同损失途径的“Trade-off”效应。对不同土壤-气候-作物体系和农田管理措施情况下,同时实现目标产量、农产品品质、降低氨挥发、硝酸盐淋洗、N2O排放和维持土壤肥力开展长期持续研究,找出同类地区的合理种植模式和施肥措施,是实现可持续集约化作物生产的关键。

| [1] |

Ravishankara A R, Daniel J S, Portmann R W. Nitrous oxide(N2O):The dominant ozone-depleting substance emitted in the 21st Century[J]. Science, 2009, 326: 123-125. |

| [2] |

United Nations Environment Programme(UNEP). Drawing down N2O to protect climate and the ozone layer: A UNEP synthesis report[R]. Kenya: Nairobi, 2013: 1-57.

|

| [3] |

Thompson R L, Lassaletta L, Patra P K, et al. Acceleration of global N2O emissions seen from two decades of atmospheric inversion[J]. Nature Climate Change, 2019, 9: 993-998. |

| [4] |

Ciais P, Sabine C, Bala G, et al. Carbon and other biogeochemical cycles[M]. Climate change 2013: The physical science basis, Contribution of Working Group Ⅰ to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Cambridge, UK:Cambridge University Press, 2014: 465-570.

|

| [5] |

Tian H, Yang J, Xu R, et al. Global soil nitrous oxide emissions since the pre-industrial era estimated by an ensemble of terrestrial biosphere models:Magnitude, attribution and uncertainty[J]. Global Change Biology, 2018, 25: 640-659. |

| [6] |

De Klein C, Novoa R S, Ogle S, et al. N2O emissions from managed soils, and CO2 emissions from lime and urea application[M]//IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories, IPCC, IGES: Kanagawa, Japan, 2006: 1-54.

|

| [7] |

Baggs E M. Soil microbial sources of nitrous oxide:Recent advances in knowledge, emerging challenges and future direction[J]. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 2011, 3(5): 321-327. |

| [8] |

Zhu X, Burger M, Doane T A, et al. Ammonia oxidation pathways and nitrifer denitrifcation are significant sources of N2O and NO under low oxygen availability[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2013, 110: 6328-6333. |

| [9] |

Wrage N, Velthof G L, Van Beusichem M L, et al. Role of nitrifer denitrifcation in the production of nitrous oxide[J]. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 2001, 33(12/13): 1723-1732. |

| [10] |

Butterbach-Bahl K, Baggs E M, Dannenmann M, et al. Nitrous oxide emissions from soils:How well do we understand the processes and their controls?[J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences, 2013, 368(1621): 20130122. |

| [11] |

Bremner J M. Sources of nitrous oxide in soils[J]. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems, 1997, 49(1): 7-16. |

| [12] |

Baggs E M, Smales C L, Bateman E J. Changing pH shifts the microbial sourceas well as the magnitude of N2O emission from soil[J]. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2010, 46(8): 793-805. |

| [13] |

Kester R A, Meijer M E, Libochant J A, et al. Contribution of nitrification and denitrification to the NO and N2O emissions of an acid forest soil, a river sediment and a fertilized grassland soil[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 1997, 29(11): 1655-1664. |

| [14] |

Wolf I, Brumme R. Contribution of nitrification and denitrification sources for seasonal N2O emissions in an acid German forest soil[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2002, 34(5): 741-744. |

| [15] |

Eichner M J. Nitrous oxide emissions from fertilized soils:Summary of available data[J]. Journal of Environment Quality, 1990, 19(2): 272-280. |

| [16] |

FAO. Global estimates of gaseous emissions of NH3, NO and N2O from agricultural land[R]. Rome: FAO and IFA, 2001.

|

| [17] |

Snyder C S, Bruulsema T W, Jensen T L, et al. Review of greenhouse gas emissions from crop production systems and fertilizer management effects[J]. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment, 2009, 133: 247-266. |

| [18] |

Venterea R T, Halvorson A D, Kitchen N, et al. Challenges and opportunities for mitigating nitrous oxide emissions from fertilized cropping systems[J]. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 2012, 10(10): 562-570. |

| [19] |

Song X T, Liu M, Ju X T, et al. Nitrous oxide emissions increase exponentially when optimum nitrogen fertilizer rates are exceeded in the North China Plain[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52: 12504-12513. |

| [20] |

巨晓棠, 谷保静. 我国农田氮肥施用现状、问题及趋势[J]. 植物营养与肥料学报, 2014, 20(4): 783-795. JU Xiao-tang, GU Bao-jing. Status-quo, problem and trend of nitrogen fertilization in China[J]. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer, 2014, 20(4): 783-795. |

| [21] |

Matzner E, Borken W. Do freeze-thaw events enhance C and N losses from soils of different ecosystems? A review[J]. European Journal of Soil Science, 2008, 59(2): 274-284. |

| [22] |

Ruser R, Flessa H, Russow R, et al. Emission of N2O, N2 and CO2 from soil fertilized with nitrate:Effect of compaction, soil moisture and rewetting[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2006, 38(2): 263-274. |

| [23] |

Snyder C S, Bruulsema T W, Jensen T L, et al. Review of greenhouse gas emissions from crop production systems and fertilizer management effects[J]. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2009, 133(3/4): 247-266. |

| [24] |

Erisman J W, Sutton M A, Galloway J, et al. How a century of ammonia synthesis changed the world[J]. Nature Geoscience, 2008, 1(10): 636-639. |

| [25] |

Zhu Z L, Chen D L. Nitrogen fertilizer use in China-contributions to food production, impacts on the environment and best management strategies[J]. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems, 2002, 63(2/3): 117-127. |

| [26] |

FAO. FAOSTAT-Emissions Agriculture-Synthetic Fertilizers Database[R/OL] [2020-03-01]. http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data

|

| [27] |

Ju X T, Xing G X, Chen X P, et al. Reducing environmental risk by improving N management in intensive Chinese agricultural systems[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2009, 106(9): 3041-3046. |

| [28] |

Chen X, Cabrera M L, Zhang L, et al. Nitrous oxide emission from upland crops and crop-soil systems in northeastern China[J]. Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems, 2002, 62: 241-247. |

| [29] |

Wang E L, Yu Q, Wu D R, et al. Climate, agricultural production and hydrological balance in the North China Plain[J]. International Journal of Climatology, 2008, 28: 1959-1970. |

| [30] |

Gao B, Ju X T, Zhang Q, et al. New estimates of direct N2O emissions from Chinese croplands from 1980 to 2007 using localized emission factors[J]. Biogeosciences, 2011, 8: 3011-3024. |

| [31] |

Zhang C, Ju X T, Powlson D, et al. Nitrogen surplus benchmarks for controlling N pollution in the main cropping systems of China[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2019, 53(12): 6678-6687. |

| [32] |

Ju X T, Zhang C. Nitrogen cycling and environmental impacts in upland agricultural soils in North China:A review[J]. Journal of Integrative Agriculture, 2017, 16(12): 2848-2862. |

| [33] |

Yue Q, Wu H, Sun J, et al. Deriving emission factors and estimating direct nitrous oxide emissions for crop cultivation in China[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2019, 53(17): 10246-10257. |

| [34] |

IFA. The Global "4R" Nutrient stewardship framework for developing and delivering fertilizer best management practices[R]. Paris: International Fertilizer Industry Association, 2009.

|

| [35] |

IP NI. 4R plant nutrition manual:A manual for improving the management of plant nutrition, metric version[M]. USA: GA, 2012.

|

| [36] |

Grassini P, Cassman K G. High-yield maize with large net energy yield and small global warming intensity[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2012, 109(4): 1074-1079. |

| [37] |

胡小康. 华北平原冬小麦-夏玉米轮作体系温室气体排放及减排措施[M]. 北京: 中国农业大学, 2011. HU Xiao-kang. Greenhouse gases fluxes of winter wheat-summer maize rotation and mitigation strategies on the North China Plain[M]. Beijing: China Agricultural University, 2011. |

| [38] |

Millar N, Robertson G P, Grace R R, et al. Nitrogen fertilizer management for nitrous oxide(N2O)mitigation in intensive corn(maize)production:An emissions reduction protocol for US Midwest agriculture[J]. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 2010, 15: 185-204. |

| [39] |

Shcherbak I, Millar N, Robertson G P. Global metaanalysis of the nonlinear response of soil nitrous oxide(N2O)emissions to fertilizer nitrogen[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2014, 111(25): 9199-9204. |

| [40] |

Kim D G, Hernandez-Ramirez G, Giltrap D. Linear and nonlinear dependency of direct nitrous oxide emissions on fertilizer nitrogen input:A meta-analysis[J]. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2013, 168: 53-65. |

| [41] |

Shepherd A, Yan X, Nayak D, et al. Disaggregated N2O emission factors in China based on cropping parameters create a robust approach to the IPCC Tier 2 methodology[J]. Atmospheric Environment, 2015, 122: 272-281. |

| [42] |

McSwiney C P, Robertson G P. Nonlinear response of N2O flux to incremental fertilizer addition in a continuous maize(Zea mays L.) cropping system[J]. Global Change Biology, 2005, 11(10): 1712-1719. |

| [43] |

Hoben J P, Gehl R J, Millar N, et al. Nonlinear nitrous oxide(N2O)response to nitrogen fertilizer in on-farm corn crops of the US Midwest[J]. Global Change Biology, 2011, 17(2): 1140-1152. |

| [44] |

Ju X T, Lu X, Gao Z L, et al. Processes and factors controlling N2O production in an intensively managed low carbon calcareous soil under sub-humid monsoon conditions[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2011, 159: 1007-1016. |

| [45] |

Gao B, Ju X T, Su F, et al. Nitrous oxide and methane emissions from optimized and alternative cereal cropping systems on the North China Plain:A two-year field study[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2014, 472: 112-124. |

| [46] |

Yan G, Zheng X, Cui F, et al. Two-year simultaneous records of N2O and NO fluxes from a farmed cropland in the northern China plain with a reduced nitrogen addition rate by one-third[J]. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2013, 178: 39-50. |

| [47] |

Cui F, Yan G, Zhou Z, et al. Annual emissions of nitrous oxide and nitric oxide from a wheat-maize cropping system on a silt loam calcareous soil in the North China Plain[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2012, 48: 10-19. |

| [48] |

Hu X K, Su F, Ju X T, et al. Greenhouse gas emissions from a wheatmaize double cropping system with different nitrogen fertilization regimes[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2013, 176: 198-207. |

| [49] |

Wang X, Zou C, Gao X, et al. Nitrous oxide emissions in Chinese vegetable systems:A meta-analysis[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2018, 239(8): 375-383. |

| [50] |

Zou J W, Huang Y, Qin Y M, et al. Changes in fertilizer-induced direct N2O emissions from paddy fields during rice-growing season in China between 1950s and 1990s[J]. Global Change Biology, 2009, 15(1): 229-242. |

| [51] |

邹建文, 秦艳梅, 刘树伟. 不同水分管理方式下水稻生长季N2O排放量估算:模型建立[J]. 环境科学, 2009a, 30(2): 313-341. ZOU Jian-wen, QIN Yan-mei, LIU Shu-wei. Quantifying direct N2O emissions from paddy fields during rice growing season in China:Model establishment[J]. Environmental Science, 2009a, 30(2): 313-341. |

| [52] |

巨晓棠. 理论施氮量的改进及验证——兼论确定作物氮肥推荐量的方法[J]. 土壤学报, 2015, 52(2): 249-261. JU Xiao-tang. Important and validation of theoretical N rate(TNR):Discussing the methods for N fertilizer recommendation[J]. Acta Pedotogica Sinica, 2015, 52(2): 249-261. |

| [53] |

朱兆良. 推荐氮肥适宜施用量的方法论刍议[J]. 植物营养与肥料学报, 2006, 12(1): 1-4. ZHU Zhao-liang. On the methodology of recommendation for the application rate of chemical fertilizer nitrogen to crops[J]. Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer Science, 2006, 12(1): 1-4. |

| [54] |

Ju X T, Christie P. Calculation of theoretical nitrogen rate for simple nitrogen recommendations in intensive cropping systems:A case study on the North China Plain[J]. Field Crops Research, 2011, 124: 450-458. |

| [55] |

巨晓棠, 谷保静. 氮素管理的指标[J]. 土壤学报, 2017, 54(2): 281-296. JU Xiao-tang, GU Bao-jing. Indexes of nitrogen management[J]. Acta Pedologica Sinica, 2017, 54(2): 281-296. |

| [56] |

Li T Y, Zhang W F, Yin J, et al. Enhanced-efficiency fertilizers are not a panacea for resolving the nitrogen problem[J]. Global Change Biology, 2017, 24(2): 511-521. |

| [57] |

Wei W, Isobe K, Shiratori Y, et al. N2O emission from cropland field soil through fungal denitrification after surface applications of organic fertilizer[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2014, 69: 157-167. |

| [58] |

Hayakawa A, Akiyama H, Sudo S, et al. N2O and NO emissions from an Andisol field as influenced by pelleted poultry manure[J]. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 2009, 41(3): 521-529. |

| [59] |

Charles A, Rochette P, Whalen J K, et al. Global nitrous oxide emission factors from agricultural soils after addition of organic amendments:A meta-analysis[J]. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2017, 236: 88-98. |

| [60] |

Burger M, Venterea R T. Effects of nitrogen fertilizer types on nitrous oxide emissions[J]. ACS Symposium Series, 2011, 1072: 179-202. |

| [61] |

Tenuta M, Beauchamp E G. Nitrous oxide producton from granular N fertilizers applied to a silt loam soil[J]. Canada Journal of Soil Science, 2003, 83: 521-532. |

| [62] |

Smith P, Haberl H, Popp A, et al. How much land based greenhouse gas mitgaton can be achieved without compromising food security and environmental goals?[J]. Global Change Biology, 2013, 19: 2285-2302. |

| [63] |

保琼莉. 华北平原旱作农田土壤N2O产生的微生物机制[M]. 北京: 中国农业大学, 2011. BAO Qiong-li. The microbial mechanism of N2O production in dry farming agricultural soil on North China Plain[M]. Beijing: China Agricultural University, 2011. |

| [64] |

Harrison R, Webb J. A review of the effect of N fertilizer type on gaseous emissions[J]. Advance in Agronomy, 2001, 73: 65-108. |

| [65] |

Granli T, Boeckman O C. Nitrous oxide from agriculture[J]. Norwegian Journal of Agricultural Sciences, 1994, 12: 1-128. |

| [66] |

Davidson, Eric A. The contribution of manure and fertilizer nitrogen to atmospheric nitrous oxide since 1860[J]. Nature Geoscience, 2009, 2(9): 659-662. |

| [67] |

Li X, Inubushi K, Sakamoto K. Nitrous oxide concentrations in an Andisol profile and emissions to the atmosphere as influenced by the application of nitrogen fertilizers and manure[J]. Biology & Fertility of Soils, 2002, 35(2): 108-113. |

| [68] |

Akiyama H, Tsuruta H. Nitrous oxide, nitric oxide, and nitrogen dioxide fluxes from soils after manure and urea application[J]. Journal of Environment Quality, 2003, 32(2): 423-431. |

| [69] |

Jones S K, Rees R M, Skiba U M, et al. Influence of organic and mineral N fertilizer on N2O fluxes from a temperate grassland[J]. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment, 2007, 121(1): 74-83. |

| [70] |

Akiyama H, McTaggart I P, Ball B, et al. N2O, NO, and NH3 emissions from soil after the application of organic fertilizers, urea and water[J]. Water Air and Soil Pollution, 2004, 156: 113-129. |

| [71] |

Ball B C, Mctaggart I P, Scott A. Mitigation of greenhouse gas emissions from soil under silage production by use of organic or slow release fertilizer[J]. Soil Use and Management, 2006, 20(3): 287-295. |

| [72] |

Akiyama H, Yan X, Yagi K. Evaluation of effectiveness of enhancedefficiency fertilizers as mitigation options for N2O and NO emissions from agricultural soils:Meta-analysis[J]. Global Change Biology, 2010, 16(6): 1837-1846. |

| [73] |

Wu D, Senbayram M, Well R, et al. Nitrification inhibitors mitigate N2O emissions more effectively under straw-induced conditions favoring denitrification[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2017, 104: 197-207. |

| [74] |

Li Q, Yang A, Wang Z, et al. Effect of a new urease inhibitor on ammonia volatilization and nitrogen utilization in wheat in north and northwest China[J]. Field Crops Research, 2015, 175: 96-105. |

| [75] |

Xia L, Lam S K, Chen D, et al. Can knowledge-based N management produce more staple grain with lower greenhouse gas emission and reactive nitrogen pollution? A meta-analysis[J]. Global Change Biology, 2016, 23(5): 1917-1925. |

| [76] |

Akiyama H, Tsuruta H, Watanabe T. N2O and NO emissions from soils after the application of different chemical fertilizers[J]. Chemosphere-Global Change Science, 2000, 2(3/4): 313-320. |

| [77] |

Yan X, Hosen Y, Yagi K. Nitrous oxide and nitric oxide emissions from maize field plots as affected by N fertilizer type and application method[J]. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2001, 34: 297-303. |

| [78] |

Subbarao G V, Ito O, Sahrawat K L, et al. Scope and strategies for regulation of nitrification in agricultural systems:Challenges and opportunities[J]. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences, 2006, 25: 303-335. |

| [79] |

Zhu G D, Ju X T, Zhang J B, et al. Effects of the nitrification inhibitor DMPP(3, 4-dimethylpyrazole phosphate)on gross N transformation rates and N2O emissions[J]. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2019, 55: 603-615. |

| [80] |

McGeough K L, Watson C J, Müller C, et al. Chadwick. Evidence that the efficacy of the nitrification inhibitor dicyandiamide(DCD)is affected by soil properties in UK soils[J]. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 2016, 94: 222-232. |

| [81] |

Gioacchini P, Nastri A, Marzadori C, et al. Influence of urease and nitrification inhibitors on N losses from soils fertilized with urea[J]. Biology & Fertility of Soils, 2002, 36(2): 129-135. |

| [82] |

Maharjan B, Venterea R T, Rosen C. Fertilizer and irrigation management effects on nitrous oxide emissions and nitrate leaching[J]. Agronomy Journal, 2014, 106(2): 703-714. |

| [83] |

Sanz-Cobena A, Sánchez-Martín L, García-Torres L, et al. Gaseous emissions of N2O and NO and NO3- leaching from urea applied with urease and nitrification inhibitors to a maize(Zea mays)crop[J]. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment, 2012, 149(1): 64-73. |

| [84] |

Venterea R T, Maharjan B, Dolan M S. Fertilizer source and tillage effects on yield-scaled nitrous oxide emissions in a corn cropping system[J]. Journal of Environmental Quality, 2011, 40(5): 1521-1531. |

| [85] |

Gao B, Ju X T, Meng Q F, et al. The impact of alternative cropping systems on global warming potential, grain yield and groundwater use[J]. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 2015, 203: 46-54. |

| [86] |

Rochette P, Angers D A. Ammonia volatilization and nitrogen retention:How deep to incorporate urea?[J]. Journal of Environmental Quality, 2013, 42(6): 1635-1642. |

| [87] |

Maharjan B, Venterea R T. Nitrite intensity explains N management effects on N2O emissions in maize[J]. Soil Biology & Biochemistry, 2013, 66: 229-238. |

| [88] |

刘敏, 张翀, 何彦芳, 等. 追氮方式对夏玉米土壤N2O和NH3排放的影响[J]. 植物营养与肥料学报, 2016, 22(1): 19-29. LIU Min, ZHANG Chong, HE Yan-fang, et al. Impact of fertilization method on soil nitrous oxide emissions and ammonia volatilization during summer maize growth period[J]. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Fertilizer, 2016, 22(1): 19-29. |

| [89] |

Engel R, Liang D L, Wallander R, et al. Influence of urea fertilizer placement on nitrous oxide production from a silt loam soil[J]. Journal of Environmental Quality, 2010, 39: 115-125. |

| [90] |

Ruser R, Schulz R. The effect of nitrification inhibitors on the nitrous oxide(N2O) release from agricultural soils:A review[J]. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science, 2015, 178(2): 171-188. |

2020, Vol. 39

2020, Vol. 39